America’s First Family of Art

Victoria Browning Wyeth gives an intimate look at a legacy of genius

By Ray Owen

Art is in Victoria Wyeth’s blood. Her family has produced three generations of such highly regarded artists that they have become part of the national consciousness. She is the grandchild of iconic artist Andrew Wyeth, the great-granddaughter of illustrator N.C. Wyeth, and the niece of contemporary realist Jamie Wyeth. Her father, Nicholas, is a private art dealer, and her mother, Jane, is an art adviser who was trained as an art historian.

“The biggest myth is that my family paints from photos,” says Victoria, a gifted photographer whose images have been exhibited nationwide. She credits a high school teacher for pushing her into a medium that was previously unexplored by her relatives. “It’s tough to come from a famous family when everyone is so talented,” she says. “I can’t paint, I have no talent, and I can’t draw a circle.”

As the designated family historian, Victoria gives lectures on all things Wyeth when not working as a therapist in the Pennsylvania state hospital system. Her insider’s knowledge of the painters has been the subject of numerous articles, and she has given talks throughout the United States and abroad, offering the public a more intimate view of her family than can be gained simply from the perspective of an art historian. She has a story for everyone of her lineage — including ties to North Carolina and Southern Pines.

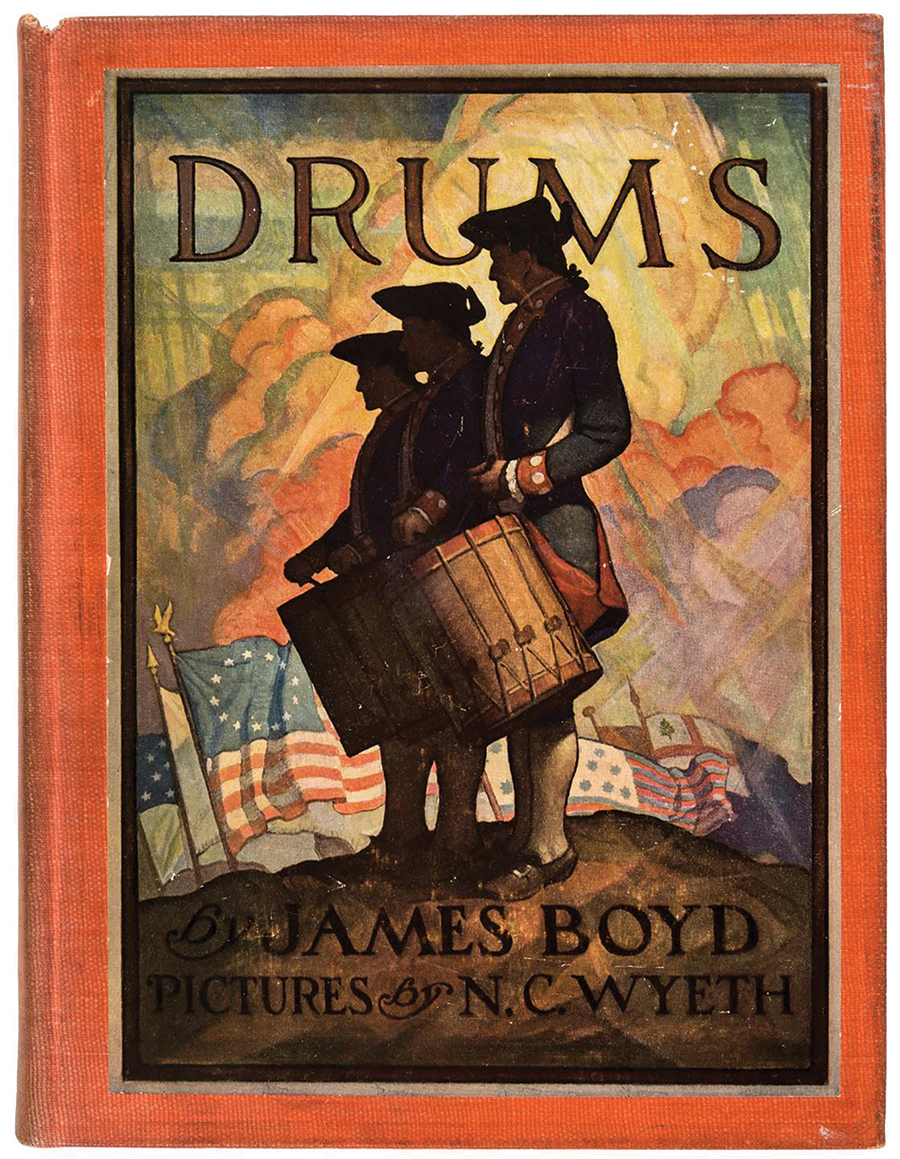

The patriarch of Victoria’s artistic legacy was her great grandfather, N.C. Wyeth (1882-1945). The town of Southern Pines owns three significant paintings by the artist that are on public display in the Utility Billing Office, located at 180 SW Broad Street, formerly the public library. The paintings, created as illustrations for James Boyd’s novel Drums, were gifted to the town by his wife, Katharine Boyd.

N.C. Wyeth was one of America’s greatest illustrators. During his lifetime, he created over 3,000 paintings and illustrated 112 books, 25 of them for Charles Scribner’s Sons publishing. A swashbuckler of a man whose works fired the imaginations of generations of readers, N.C. Wyeth was a household name during the first quarter of the 20th century for the art he provided for classic titles like Treasure Island, The Last of the Mohicans and The Yearling.

Standing larger than life, N.C. Wyeth was a realist painter whose dramatic canvases could be understood quickly. He only painted from experience, sympathetic to his subjects, showing them at one with their environment. It was this interest that brought him to Southern Pines in 1927, in preparation for his illustrations for Drums. Boyd was making a name for himself in literary circles, his Weymouth mansion a favorite retreat for such figures as William Faulkner, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Thomas Wolfe.

There was a wonderful exchange of letters between Wyeth and Boyd included in an early 1928 edition of Drums. Boyd provided a car and driver for Wyeth for a side trip to Edenton, North Carolina, so that he could get the look and feel of the Colonial town, the setting for the book:

N.C. Wyeth, Edenton, NC, December 1927

My dear Boyd,

This afternoon was spent wandering in and about these relics of 1770. My heart went out to them, because you, Boyd, have made them alive for me. The oak timbers, whose adze-marked surfaces are still crisp on their protected sides and smoothed to gentle undulations where the sun and rain for years have touched them, thrilled me like music.

Cordially, Wyeth

And the reply:

James Boyd, Southern Pines, NC, December 1927

Dear NCW,

Your letter just come from Edenton disturbs me. It is an injustice of nature that a man who can paint like you should also be able to write like that. Everything you say stirs me mightily. It is only the way you say it that makes me uneasy. A little tactfully assumed illiteracy would be more becoming when addressing a man in my business. Otherwise I might be obliged to ask myself why I am in this business at all.

In its day, Drums was considered the finest novel of the American Revolution that had ever been written, with more than 50,000 copies sold in its first year. Since that time, generations of Southern Pines residents have cherished the Wyeth paintings as an important aspect of the cultural heritage of the town.

Victoria Wyeth’s personal connection to Southern Pines is through her acquaintance with artist Jeffrey Mims, founder and director of the Academy of Classical Design. As a painter and educator, Mims has been at the forefront of the revival of the classical tradition for the past 30 years.

For Victoria, her Uncle Jamie (b.1946) is the keeper of her family’s tradition, with his paintings more varied than his predecessors. “Jamie is the future of our family,” says Victoria. “And he’s so different. He’s managed to do his own thing in his own style, and he’s painted everything from pigs to presidents. The whole family has a wonderful sense of humor, and Jamie’s the one who paints with it.”

Jamie’s father, Andrew Wyeth, holds a very special place in Victoria’s heart. As his only grandchild, she was one of the few people he ever allowed to watch him paint. The first photograph she took of her grandfather was a kind of epiphany. “I always saw him as this adorable, smiling older man,” she says of that day. “For the first time in my life, Andrew Wyeth was standing before me. Not Grandpa, but the artist, and he had the most earnest look I had ever seen in my life.”

Andrew Wyeth (1917-2009) is recognized as one of the most important American artists of the 20th century. For more than seven decades he painted the regions of Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, where he was born, and mid-coast Maine, where he spent most of his summer months.

The youngest of N.C. Wyeth’s five children, at age 15 Andrew began several years of intensive artistic training under his father, who encouraged him to work as both an illustrator and painter. His career launched in 1937 with a sold-out exhibition of his watercolors in New York. On the occasion of the young artist’s debut, his father wrote him a congratulatory letter prophesying, “You are headed in the direction that should finally reach the pinnacle in American art.”

An austere poet laureate of rural life, Andrew once noted that meaning “is hiding behind the mask of truth” in his work. He freely manipulated his subjects, transforming them in order to evoke memories, ideas and emotions. Through a process of reduction and selection, he created mysterious undercurrents in his landscapes, interiors and portraits.

Victoria adored him, called him “Andy,” and spent all her childhood summers with him and Grandma Betsy in Cushing, Maine, where she vividly remembers long boat trips to family-owned islands for picnics. As a child, Victoria began to realize that “all the people in the paintings were the folks I’d been hanging out with,” and she fondly recalls that, “on Andrew’s birthday the president would always call.”

Andrew drew and painted Victoria many times. She was 6 years old for the first sitting and remembers very little about the experience, except how hard it was to keep still. “We had made a deal the third time that I’d only pose if I could take notes, and so I just sat there taking notes the entire time.” The artist often chuckled at her precociousness, but he gamely tried to answer every query.

The last question logged in her “Andy Journals” was about how to create the color black. He said that he didn’t start by squeezing inky paint from a tube. “You build in the excitement before adding black, you slowly build it up with blues and reds and greens.”

One of Andrew Wyeth’s most powerful works is in the permanent collection of the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh. The painting, titled “Winter 1946,” depicts a boy running fast and recklessly down a hill, casting a long shadow on the grass behind him. The figure with furrowed brow, gazing down and forward, is dressed in a heavy winter coat, his mind elsewhere, lost in the golden earth, and the vast, breathtaking landscape.

Andrew created this painting after the horrific death of his father in 1945. The tragedy occurred at a railroad crossing on a hill in Chadds Ford, when an oncoming train hit the car carrying N.C. Wyeth and his young grandson, killing them both. The hill became a source of inspiration for Andrew’s paintings over the next 30 years, as he rendered the memory of the place into something strangely beautiful.

Victoria Wyeth’s most enduring memory of her grandfather is not paint and canvas, but “his hugs — he gave the best long hugs. He made me feel so special all the time.” During his lifetime Andrew said, “Your art goes as far as your love goes.” PS

Ray Owen is a local historian, who works for the Arts Council of Moore County.