Going all-in out in the country

By Jim Moriarty • Photographs by Tim Sayer

Jimmy Stewart had one in Harvey. His pooka was a benign rabbit, unseen by most of humanity, that was precisely 6 feet 3 1/2 inches in height. Stewart’s character, Elwood P. Dowd, was a known and decidedly content tippler. “Well, I’ve wrestled with reality for 35 years,” says Dowd to the doctor who was passing judgment on his lucidity, “and I’m happy to state I finally won out over it.” While these creatures of folklore can take many forms, one wonders just how much wine would be necessary to make two otherwise sensible, urban-dwelling people, Sue Stovall and her late husband, Hunter, see goats.

“The story is well known that we had too much wine one night and decided to buy goats,” says Stovall. “Very good wine. There was a lot of it probably.” And so Paradox Farm was propelled down its dirt-road, cloven-hoofed path.

The farm began in 2007. “It was about the time the economy was changing,” says Stovall. “Hunter and I were both self-employed. He was an attorney, the kind who enjoyed more counseling than litigating. He would rather help you solve a problem than litigate a problem. I was in health care. We worked 3 miles from where we lived (in downtown Southern Pines). Let’s move out to the country. We bought this house. It was a horse farm. We were here for about a year trying to figure out what we wanted to do.”

A few chickens, which are apparently the gateway species to serious livestock, showed up first. The hens were followed by an evening of red wine, a llama and three goats. The first two goats were named Thelma and Louise. “There was never, ‘Oh, I always wanted to be a farmer.’ Everything was like, ‘Hey, let’s try this,’” says Stovall. “I’m probably the most unplanned person you ever met. So, we got the goats and we had babies and started milking goats and started making cheese. We were sitting on the porch and drinking wine and eating our cheese and looking at this book about how to make your own creamery. It starts listing 10 things you should want to do if you want to do a dairy, because it’s really hard work. We looked at all of them and we’re, like, ‘None of those fit. Let’s do it!’”

By 2011, Paradox Farm was a licensed creamery. “Since then we’ve been growing the herd, making and selling cheese, and expanding our markets,” says Stovall. She hasn’t done it alone, but she has done much of it without Hunter. Sue grew up in Plainview, New York, in roughly the geographical middle of Long Island, near Bethpage State Park. She has three degrees in physical therapy, including a Ph.D. from Boston University. Hunter grew up in Virginia, went to the University of Virginia and Campbell University School of Law. Hence the “pair of docs.”

By 2011, Paradox Farm was a licensed creamery. “Since then we’ve been growing the herd, making and selling cheese, and expanding our markets,” says Stovall. She hasn’t done it alone, but she has done much of it without Hunter. Sue grew up in Plainview, New York, in roughly the geographical middle of Long Island, near Bethpage State Park. She has three degrees in physical therapy, including a Ph.D. from Boston University. Hunter grew up in Virginia, went to the University of Virginia and Campbell University School of Law. Hence the “pair of docs.”

Just as their porch reading advertised, a dairy is hard work. “We would get up in the morning. He would feed and I would milk. We’d go in the house, take a shower, change our clothes and go to work. Come home, change our clothes, feed and milk and do whatever we needed to,” says Stovall. “On weekends we would go to markets. I was doing Southern Pines and he was doing Cary. We had both gone to market that morning, which means he had to leave about 6:15. He went to market, came home and lay down to take a break before evening activities, got up and had a heart attack.” That was four years ago this August.

Stovall has two daughters who are Moore County residents, Ariel Davenport, who owns Set in Stone/The Slab Warehouse, and Kassia Stubbs, who works for Moore County Schools. Her son, Mike Kowalick, lives in Seattle, Washington. “My girls are not farm kids at all but they support my efforts,” says Stovall. Her son helps with strategic plans — how to lower the power bill, marketing ideas, etc. It was Mike who suggested his mother engage interns from World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms. “He was trying to figure out how I was going to survive without Hunter,” she says. Beri Sholk from Orlando is there now, the sixth WWOOF intern who’s worked at Paradox Farm, trading labor for knowledge, something that’s turned out to be a two-way street. The interns have been from California, Florida, even the Republic of Mali, West Africa. “It’s really expanded my world,” says Stovall.

The goatherd at Paradox Farm stays roughly level at around 40, though the number jumps when the season’s kids are born and before they’re sold. “I started with Nigerian Dwarfs because they were cute and little and I thought I could handle them,” says Stovall. “Then I added Nubians. Then I needed to get more milk so I added some Alpines.” All the goats have names. The ones that look alike wear identification tags. And, no, they don’t say “Hello, My Name Is . . .”

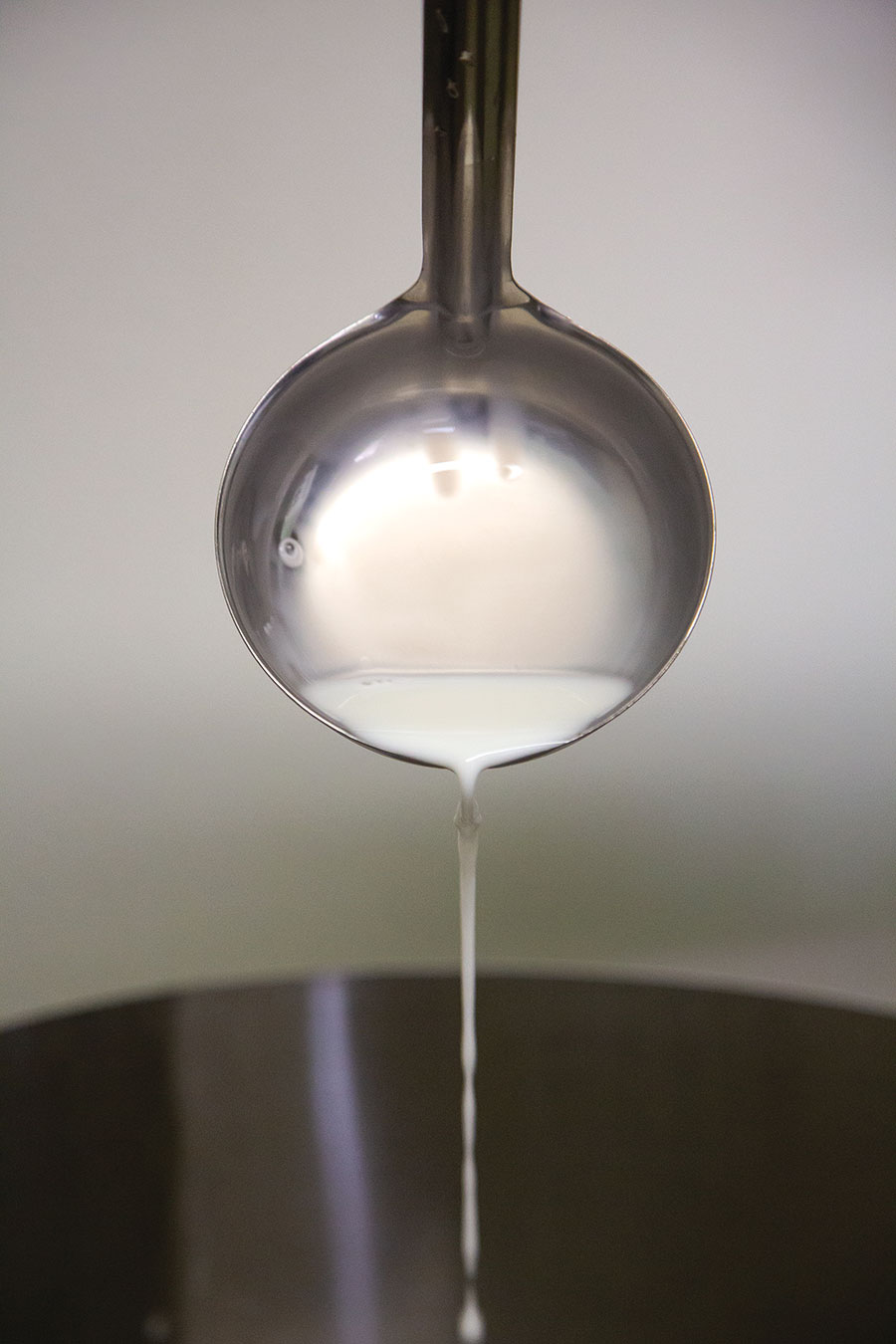

They milk 22 goats a day, two at a time, using a pumping machine. In a large dairy the milk from 10 times the number of stanchions would travel through pipes to a bulk tank. “Because we’re small, we just pick up our buckets of milk and pour them in a tank,” says Stovall. “I think it really helps in the quality of our cheese because milk is a molecule, a living organism. The less you handle it the better it’s going to be. Our cheese tends to be sweeter and milder than most people think of goat cheese.”

The 61-year-old Stovall’s skills from her previous occupation can come in handy, getting the kinks out of a farm hand’s neck, fixing a goat’s broken leg, or putting a brace on Beri’s left arm after she was kicked — the goat version of negative feedback. “Farming is a full-contact sport,” says Stovall.

The Paradox Farm cheeses show up at places like Southern Whey and Nature’s Own in Southern Pines, the Corner Store in Pinehurst, Black Rock Winery and restaurant’s like Ashten’s and 195, just to name a few. Wrapped, infused, washed and aged, the flavors (and puns) are as wide-ranging as the names would suggest: Drunk N Collard; Sweet Hominy; Red Eye, Feta Complee, Paradox Paneer and Cheese Louise!

Making a small farm sustainable, however, is a value-added proposition. With the help of a grant from the University of Mount Olive, Stovall bought an old tobacco barn, broke it down and reassembled it on her farm. Half of the barn will be a cheese cave for aging. The other half will amount to a mini-storefront. “We do farm events. The last couple of years we’ve had hundreds of people come out on a Sunday afternoon, tour the dairy, see the goats. We do ‘Goat Yoga’ once a month. And we have pairing events where we pair cheese with something. Our first one was beer and cheese. We’re doing cheese, wine and desserts with Black Rock and the Wine Cellar. I’m determined to make this work,” says Stovall.

“One of the biggest challenges for me over the last couple of years is to learn to farm smarter. These are my babies. When they die I’m going to burn sage and say a little prayer when I bury them. I still have to be able to balance that need for myself with the business of running a farm. It’s a challenge to find that balance. Every day is filled with disaster and beauty.”

Paired, perhaps, with some Cheese Louise! and a petite shiraz. PS

Jim Moriarty is senior editor of PineStraw and can be reached at jjmpinestraw@gmail.com.